I’m fascinated by the uncanny.

When writing about this cognitive phenomenon, it is customary to kick things off with Sigmund Freud and his 1919 essay, ‘Das Unheimliche’, which, for my money, rather spoils things a bit. The problem with the uncanny is the very act of describing it makes it harder to comprehend; all that is nice and slippery about the sensation dries up on the page, frightened off like an evasive sneeze.

I’ll begin instead by recounting my first encounter with this mercurial sensibility. I was very small, and in the way of small children everywhere, I hadn’t yet understood that time passes when you’re asleep. I’m reminded of that famous jump-cut at the beginning of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: a Space Odyssey, where the ascending bone becomes the descending satellite—four million years of evolution dispensed with in the blink of an eye.

When I went up to bed on this one particular night, I’d left mum and dad watching television in the living room of our council house. This was the late seventies you understand, so there was the nylon carpet, everywhere chocolate brown gloss paint and gauze of cigarette smoke.

When I think about it now, I imagine this domestic scene lit by the blue strobe of our boxy tv and the orange glow of our inadequate gas fire. Whatever the truth of that, it was what home looked like, so coming back downstairs to find the living room empty, and my parents vanished, came as a terrible shock.

As far as I was concerned, I’d only been asleep for a matter of seconds before heading back down for that pretend glass of water; and it wasn’t quite the darkness, or the gone-ness of my parents, but rather the wrongness of what was otherwise right. This was my house, but also not; it was at once ‘home’ and ‘not’ home. It was un-homely; unheimlich.

The Witch’s House

Years later, I would read something that explained this unnerving moment back to me. In Das Unheimliche, Freud does something fascinating with the etymology of ‘home’. Looking to the synonyms of the word itself, Freud follows them like a trail of semantic breadcrumbs; he gives us ‘home’ as connoting somewhere safe, and home as secure, home as private; then home as a hiding place, home as secretive, as threatening, as frightening…

Breadcrumbs is right: poor Hansel, poor Gretel, always tracking deeper into the haunted forest and ever closer to the witch’s house.

For me, at least, the uncanny is as simple as that: as ‘simple’ as taking an ordinary strip of paper, and from it, making a Möbius strip, that topological curiosity that enables you to trace a path along both its sides without once crossing an edge. In common with that simple twist of paper, the uncanny is where things we know to be logically separate, or in opposition, are not just joined, bridged or blended, but give rise to each other.

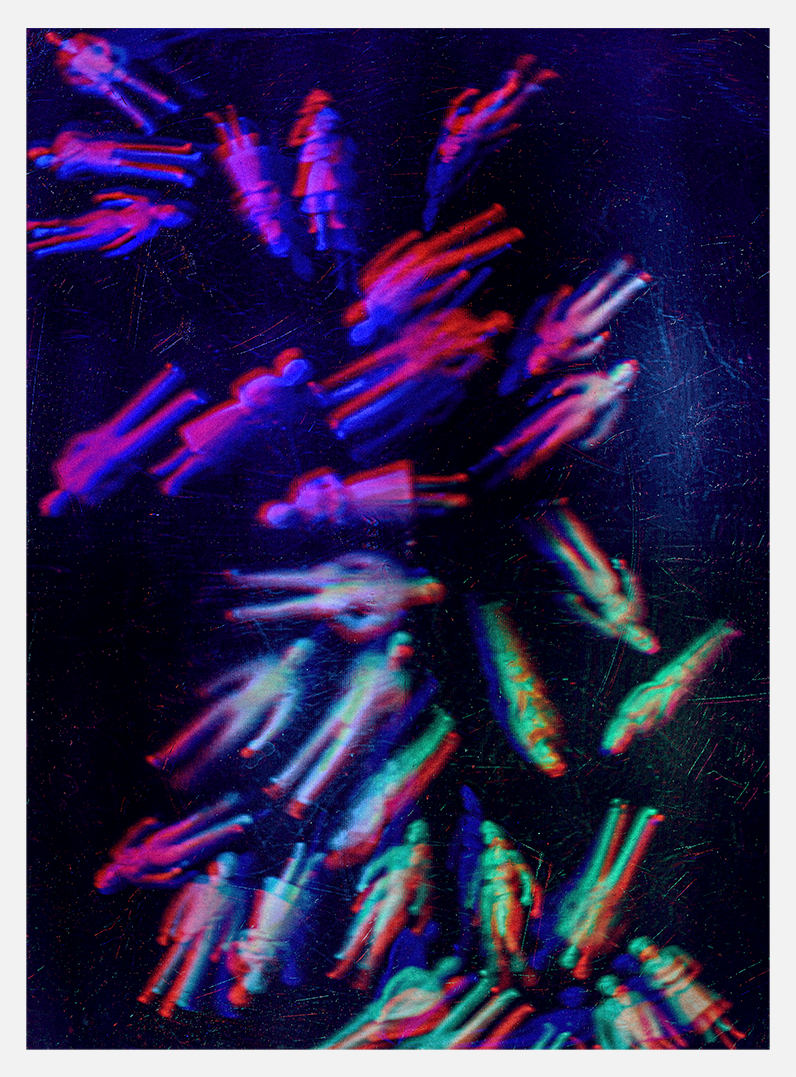

This is why waxworks and mannequins are uncanny artefacts too, for they are us, and also not us; likewise our own reflections and self-portraits. You need only consider the proliferation of superstitions that associate with the semblances of ourselves: I give you the breaking of mirrors bringing bad luck, and doppelgängers as auguries of our own impending doom. Who amongst us would comfortably stick pins into the images of family members (you don’t have to answer that), and why is it that ‘evil twins’ are the subject of so many hokey storylines in soap operas?

The Same As It Is Wrong

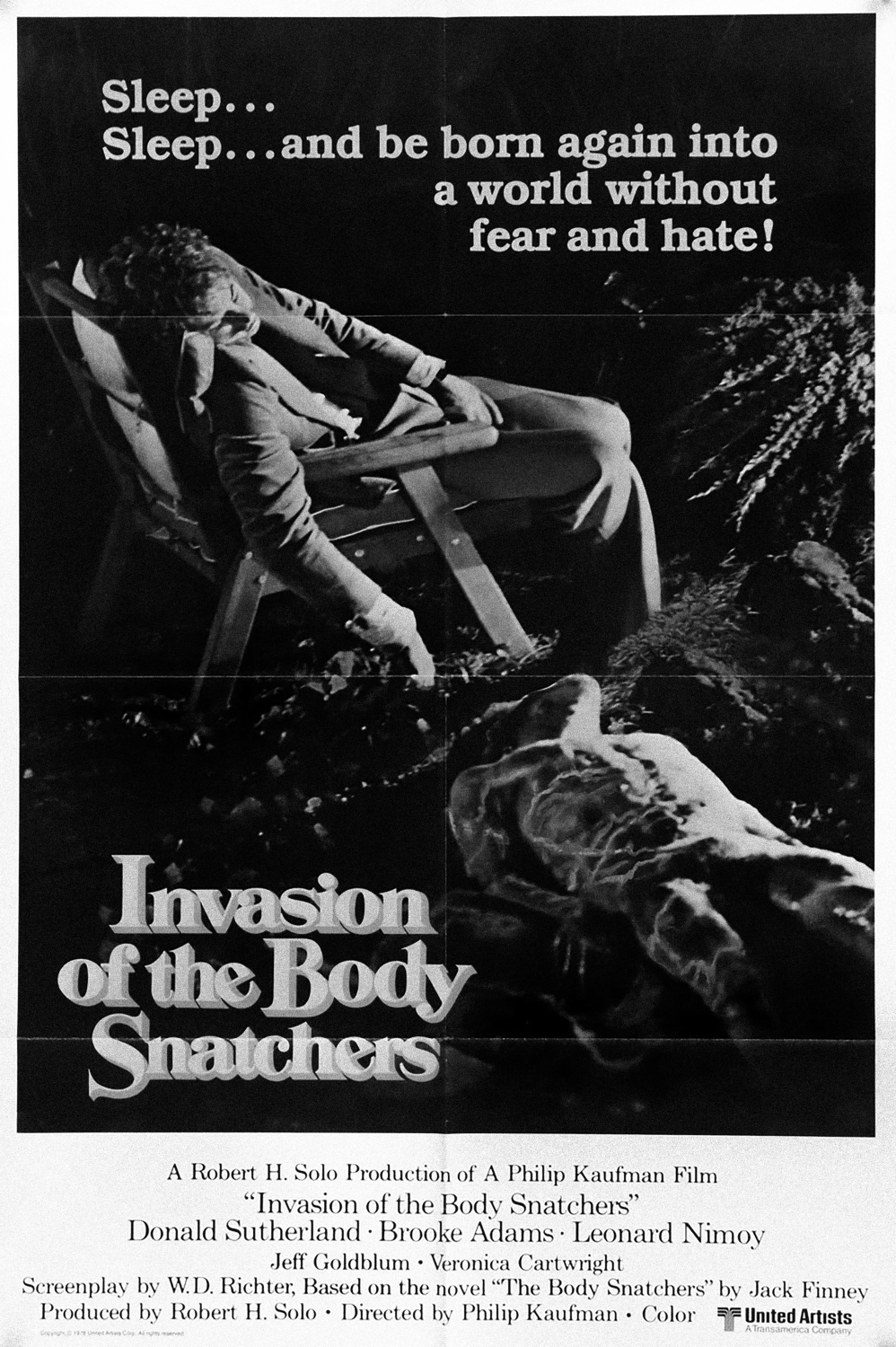

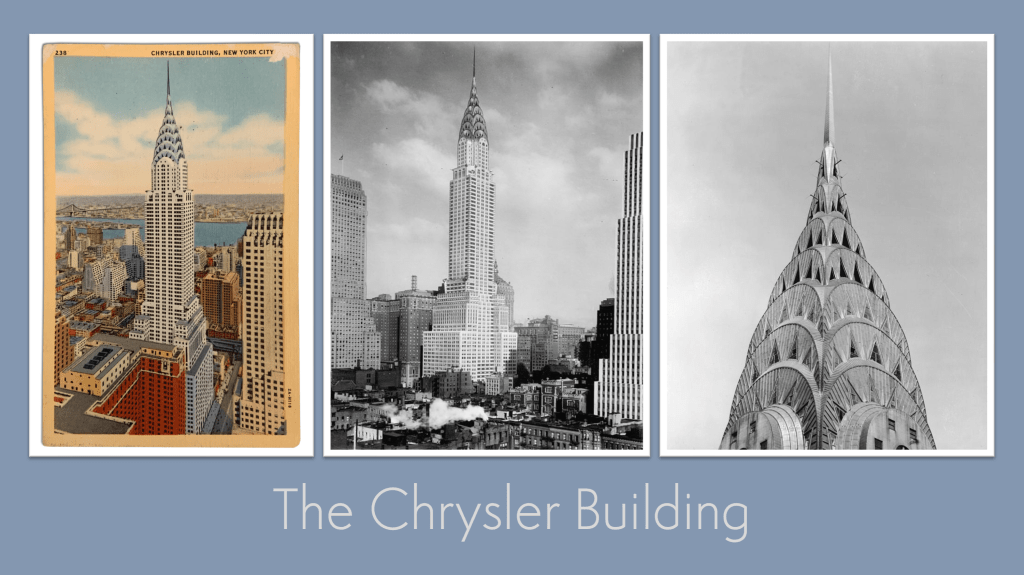

Don Siegel’s 1956 science-fiction film Invasion of the Body Snatchers is hokey too, with its outlandish plot, in which the nice people in one of those nice American towns are replaced by identikit, hive-minded aliens bent on world domination.

Outlandish it maybe, but Seigel’s film is terrifying and one of my favourite things. It is as Anthony Vidler observes; “For Freud, ‘unhomeliness’ was more than a simple sense of not belonging; it was the fundamental propensity of the familiar to turn on its owners, suddenly to become defamiliarized, derealized, as if in a dream.’

In Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the horror comes, not from its set-pieces, so not the frothing pods birthing doppelgängers in the greenhouse, but from the protagonist’s powerlessness to do anything about it. His world is the same as it is wrong, as unchanged as it is counterfeit. Reality has been captured, proxied, and no one is listening because, to quote a chilling line of dialogue from Abel Ferrara’s 1993 Body Snatchers remake, ‘There’s no one like you left.’

In one of cinema’s bleakest endings, we see the hero of Siegel’s original waving cars down in the street, shouting, ‘They’re already here! You’re next!’

The night I came downstairs, the unhoming of my safest space happened in an instant, rather like that sequence in John Carpenter’s They Live (1988), in which Roddy Piper puts on a pair of sunglasses that show him, in stark black and white, that in common with Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the aliens live amongst us and ‘the real’ is a lie.

For me, at least, my cognitive dissonance was short-lived, my parents magically reappearing from their own bedroom to switch on the living room light. Normality was restored, though, for some time afterwards, I eyed the fixtures and fittings of my home with suspicion, as someone might stare at the family dog that turned around one day and bit them.

In Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the dopplegänging of an entire community and its institutions is slower and more insidious—though there are red-flags from the outset. As one character observes about another in an early scene of the 1956 original: “You know her uncle, Uncle Ira?… She’s got herself thinking he isn’t her uncle. She thinks he’s an imposter or something”.

And now I think about it, there were signs at the very beginning of my university teaching career: small changes in otherwise respected colleagues; glitches, tics, sudden outbreaks of homogenous language… but, as is common in narratives of this kind, I didn’t join the dots until much later.

You’ve Gotta Take Good Aim

Anyway, back when I was wearing paisley pyjamas and coming downstairs for glasses of water I didn’t want, games like dot-to-dot were already really boring. There was another game I wanted to play much more, a colourful, clacking, plastic thing, the advert for which was always on our big boxy television. The game was called Hungry Hungry Hippos, and the jingle went like this:

If you wanna win the game you’ve gotta take good aim

And get the most marbles with your hippo

Playin’ Hungry Hungry Hippos

Hungry Hungry Hippos

Mum and dad never found their way to giving me Hungry Hungry Hippos, (something about me waking them up in the middle of night by screaming the house down I suspect), but the tv advert made the goal of the game completely clear: each of its four players had to chomp as many marbles as possible by very aggressively banging their respective plastic hippo, so each hippo’s mouth shot forwards to gobble down more marbles more quickly than anyone else’s.

These days, when I’m watching my much-less-boxy television, listening to some swivel-eyed former prime minister banging on maniacally about ‘unleashing Britannia’ or blowing smoke about the axiomatic benefits of neoliberalism, all I hear is the jingle to the Hungry Hungry Hippos commercial. All I see are those four plastic hippos, uniform and charmless, gobbling everything up.

For the record, neoliberalism, as an economic and political ideology, promotes minimal government intervention in markets and underscores individualism, competition, and the commodification of services. In the context of higher education in the UK, neoliberal policies have accomplished the marketisation of universities, transforming them into competitive entities vying for student fees—or, to put it another way, “If you wanna win the game, you’ve gotta take good aim.”

Neoliberalism has redefined the role of students too; they are consumers first and learners next, with universities adopting customer-centric approaches that reconfigure the student experience as a product. Accordingly, universities rely on metrics and performance indicators to gauge their success, which they can then ‘take to market’ in the form of league table results and statistics writ large on billboards, buses and TikTok.

These metrics typically encompass recruitment and retention rates, numbers of ‘good degrees’, student satisfaction scores, and graduate destinations. Commitments to diversity and equal opportunities have likewise become valuable marketing collateral for universities (which is a word I can never hear used without seeing dead bodies).

Back when I was first teaching in a university, I wasn’t thinking about neoliberalism—neo-what? I was just trying to get my one small bit of the jigsaw to fit like I thought it should and not look like a dick in front of more experienced people. I was worrying about how to turn on the projector and keep it on; how to make a software induction on the inner workings of Final Cut Pro a little less deadly for year two photographers; how to explain the Kuleshov effect; how to justify showing Jaws again because—da dum da dum—I bloody loved it; and how to be cool and truthful and kind.

Really, I just wanted my students to like me, but as I said, there were signs even then that Uncle Ira maybe wasn’t Uncle Ira after all.

A More Painless Existence

I met my first pod person at a course board.

It was that serious time of year when faculty gathered warily in a largely airless room to agree the exit awards for their students under the gimlet eye of Quality Assurance. I say ‘warily’, because, at that time, the Head of Quality was openly hostile towards the warts-and-all of student achievement, which he communicated in the form of his deep disdain for the academic judgements of plebs like me.

While hardly the mighty Colosseum of Rome, our course boards were a battleground between the lived experience of the students who came to study with us and the statistical bell curve our Head of Quality seemed to prefer over the messier activity of actual people. No one enjoyed this spectacle very much. It was dreaded mostly, especially by younger staff, of which I was one. There were losses on both sides, but the clash was always felt to be an important one, because it was a philosophical conflict between ‘Quality’, taken to mean ‘Value’—i.e. the value course teams placed on assessment as a record of ‘what actually happened and how’—and ‘Quality’ connoting ‘Standards’, meaning benchmarks set by external bodies, regulatory authorities, and statistical precedent.

This particular course board began as normal, with each of us taking our seat with all the enthusiasm of prisoners lining up before a firing squad. One by one, we took our chances, unspooling the long ticker tape of our students’ grades for the approval—or otherwise—of a single individual who enacted an institutional model of what ‘good’ looked like.

When the turn came for one of the university’s more formidable lecturers to go before ‘the man’, we braced ourselves for the inevitable skirmish. We needn’t have worried. With no resits, retakes, or fails, and with just the right number of thirds, a lovely bulge of 2:2s, a sprinkling of 2:1s, and the scantiest number of firsts, this lecturer’s student grade profile was practically perfect in every way. The Head of Quality blissed out, this role-call of optimum results having the same effect as one of those plug-ins used to tranquillise cats.

Bloody well done!

Except my colleague’s expression was odd. They looked pleased, of course; they’d played a perfect hand of cards and now the big bad wolf was kittenish, but their smile…

Thinking about that smile now, I’m reminded of Jordan Peele’s Oscar-winning film Get Out (2017), specifically those wonderfully unheimlich scenes in which the consciousness of one person buried inside the shell of another resurfaces unexpectedly. For my part, I couldn’t quite make up my mind what I’d witnessed; a shining example of pedagogic excellence (it happens), a fluke, (they happen too), or maybe something unheimlich?

In Philip Kaufman’s 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, there is a fun, creepy moment when the fibrous lamina covering the body of a developing replicant ambulates suddenly to reach out and touch the hand of the human it is in the grim business of replacing. What I observed in that course board was something similar I think; my first brush with an implanted intelligence offering all of us a more painless existence in exchange for our nuance.

The Business Of Replacement

My second encounter with a pod person came much later.

By now, I was working as a senior lecturer on a different course. I was sitting with my colleague over a cup of crap coffee, and my colleague was ashen with rage. He’d just been informed by our then Head of School that he was required to change his original profile of marks for a particular module before they would be submitted to the registry for inclusion in the system.

The Head of School was unhappy with the number of students who had failed to meet the assessment requirements on their first attempt and wanted my colleague to ‘look again’ at his decision-making. True enough, it was a higher-than-normal number of fails, or, more accurately, higher than in some previous years. The Head of School hadn’t themselves read the project brief in question, engaged with the delivery of the module, or was in any way conversant with the students themselves or their particular sets of circumstances. He just didn’t like the optics. He wanted different statistics, preferable statistics.

Had the Head of School been thinking about the student experience, he might have regarded this performance data as litmus paper; a showing-up of insights in potentia, the significance of which we could determine to the benefit of learners.

We could have enjoyed a creative chat about how to improve the design and delivery of this particular module, looking at everything from the quality of the learning resources to the timetabling of hand-ins to ensure students had more time with the printers in the library…

We could have discussed how to better onboard individuals from non-traditional backgrounds, by first acknowledging the socio-economic realities of our institution’s geographical location…

We could have looked properly at the diversity of our cohorts and the suitability of our recruitment practices…

We might also—imagine!—have discussed the pedagogy of failure. I’m not talking about the merits of making people feel like failures (there are none), but the idea that some things come more easily to some than to others, and passing someone for work they haven’t done, for knowledge they do not yet have, for experiences they cannot yet embody or use to their own benefit, is an exclusionary act like no other and a clear abuse of institutional power.

Who knows, we might also have had a constructive chat with my colleague—to see if everything was okay with him, to see what he thought was going on, or to see if he needed more support…

Had our Head of School been thinking about my colleague at all, he would have known that, by making this singular request of him—asking him to bowdlerise his own academic judgement for the purpose of producing more agreeable percentages—he’d scooped out this person’s sense of self as cleanly as any of those brain surgeries in Jordan Peele’s Get Out. Gone now was this person’s professional confidence and, in its place, a hot, bright ball of nuclear-grade cynicism for the whole project of our institution thereafter.

But, as I think we’ve determined, our Head of School wasn’t thinking about my colleague’s self-esteem or the esteem in which my colleague once held the university, just as he wasn’t thinking about our students’ access to an equitable learning process. He was thinking instead about how my colleague’s set of metrics might look once set against someone else’s—or rather how our Head of School’s performance as a manager might look once set against the performances of his direct competitors, I mean, other Heads of School, in the marketplace—whoops, I mean, university.

This pod person was much further gone than the one I encountered at that course board. ‘Pod Person One’ had finally succumbed to the dulled, happy-sad understanding that it was comfier professionally to ‘think a little less and feel a little less’ in exchange for an easy life—given the fact that the then-Head Of Quality was a red-faced man in the business of shaming academics for a) using the full range of marks out of 100% available to students, and also b) not using the full range of marks

‘Pod Person Two’ was more like the town folk in Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers; not just replaced, but in the business of replacing.

Looking out of the window of his hiding place, the film’s protagonist witnesses a truck arriving in the town square, whereupon the community, of which he was once part, rush to unload more pods from the back of it, hurrying them away so as to seed more replicants far and wide. This is how our hero comes to learn his pod person problem isn’t localised. This is how we learn the pod people are coming for all of us.

Imposters

My third encounter with pod people saw me sitting across from two individuals who, to all intents and purposes, looked exactly like our university’s Vice Chancellor and Deputy Vice Chancellor respectively.

My meeting with them was about how course leaders, as I was by then, could seek to bolster their National Student Survey results to improve the university’s position in those all-important league tables.

To be honest, I was in a much better position to be telling them how to do it. Had I been asked, I might have talked with some enthusiasm about the quid pro quo between the design and delivery of exceptional learning experiences and contented communities of students, and said how a thing like that surely wasn’t rocket science, and if this was coming as news then God help us all.

Besides, I already knew what I wasn’t allowed to do in terms of facilitating the student survey, which was still voluntary regardless of its importance to all those hungry hungry hippos. The guidance around presenting the survey to our students was always crystal clear: you don’t coerce, you don’t bribe, and you don’t curry favour. This was the student survey, so I even drew the line at timetabling sessions for completing it and never provided donuts or offered students lollipops for being good.

So, imagine my surprise, when the VC said, ‘You need to tell your students that giving poor student satisfaction scores will reflect on the quality of their degrees and impact their employability!’

I glanced at the DVC. I was looking for a twitch, a glimmer of shame, but their expression was blank. Just to be clear, the VC’s advice was in flagrant contradiction, not only of all official guidance regarding undue influence, but ran contrary to the whole point of the survey, which, however flawed, was incepted to produce knowledge, not replace it.

So, there I was, by now nearing the end of my career as a university lecturer, and sitting across from two expensive vegetables as hollowed out as gourds.

And here’s another thing that isn’t rocket science: that targets only work to undermine, distort, or bowdlerise whatever phenomena they’re trying to galvanise, and they do so because targets are mechanistic—or rather, human beings are. Let’s paraphrase Vidler: ‘Unhomeliness’ is more than a simple sense of not belonging; it is the fundamental propensity of the familiar to turn on its owners.’

And let’s take a short pause to imagine another trail of breadcrumbs: target meaning goal > goal meaning aim > aim meaning mark > mark meaning quarry > quarry meaning victim > victim meaning target… and that’s another Möbius strip right there.

The Conference

A few years before two senior dopplegängers advised me to bribe students into giving false information to more effectively productise the university’s student experience, I was approached to speak at a teaching and learning conference. I was approached because, historically, the course I led returned consistently high scores in the same student survey I would later be encouraged to skew.

The truth is I didn’t want to participate in the conference. After the yearly survey scores were published, the university would circulate all course results to all staff via our emails. Senior leadership didn’t need to do it this way, but they did, and they did it to produce winners and losers; to elicit shame and stoke competitiveness.

Now that I was aware of the impact of neoliberal policies on education, I saw this management practice for exactly what it was; another vulgar, clacking round of Hungry Hungry Hippos encouraging a bunch of really quite sophisticated grown-ups to fight for their institution’s approval like kids fighting over marbles.

Given my course scores, and given the way the university used them to ‘punch down’, I’m pretty sure many of my colleagues had come to think of me as a fully signed up member of Pod Person Incorporated. “But how are you doing it?” one course leader asked me slyly, as someone might ask a flashy magician who can’t be making their assistant disappear but is disappearing them anyway.

I agreed to speak at the learning and teaching conference on one condition: that I would be free to talk about my other statistics too. Not all my metrics were as lauded as those helping the University claw its way up those less-than-reliable league tables in its continuing race to the bottom. I had higher-than-desirable numbers of first-year students taking more than one attempt to meet their learning outcomes; I had higher-than-desirable numbers of students taking interruptions of studies. I had too many firsts and not enough firsts. I had too many thirds and not enough 2:1s, or sometimes too many 2:1s and not enough 2:2s.

Turns out, the Wizard of Oz was a bit of a mess when you looked behind the curtain—and it looked that way because I defended the right of my students to fail and the right of my staff to fail them. I likewise defended the right of my students to achieve 90% or higher if that was our judgement, or for no students to get firsts when there weren’t any firsts. I similarly defended the right of my students to take a break, to pause, to regroup; to leave and come back or drop out and do something more apposite if my course really wasn’t right for them.

I was far from popular at those latter course boards, and I had to expend a lot of extra energy justifying why I wouldn’t be making my metrics more attractive to the various non-student facing consumers of my course’s statistical information. It was exhausting for everyone.

Wonky Veg

I called my conference presentation ‘Wonky Veg’, after the ludicrous situation in which supermarkets refuse to stock perfectly good produce if the fruit and veg in question are deemed too imperfectly shaped. At some point, apparently, it’s been accepted as self-evident that a less-than-straight carrot is something ‘less’ than a carrot.

This is a logic born not of anything we might recognise as sensible or sustainable, or wise or good or accurate, but of the market. As so-called logics go, it has enormous power to devalue and make waste, not only by privileging ‘the idea of something’ over its substantive form but by projecting and duplicating itself as ‘true’ in the imaginations of others

There is a great scene in the 1974 film version of Ira Levin’s novel The Stepford Wives, a narrative in which the women who live in another of those nice American towns have been replaced by beautiful, obedient robots, modelled after the exact image of the human beings they’ve substituted – only better. Early on in the story, the film’s hero, Joanna Eberhart, a former New Yorker newly arrived in Stepford, instigates an informal discussion group to problematise gender roles. The discussion soon takes a chilling turn when the women in the group default to their programming, which sees them rhapsodize over the virtues of spray-on starch.

Fittingly, the bleakest moment of The Stepford Wives takes place in a supermarket and, spoiler alert, poor Joanna is now a replicant too. As the film concludes, we see Joanna and the rest of the robot wives gliding past shelves stocked from top-to-bottom with identical products and the film’s message is clear: there is nothing normal, desirable, healthy or humane about homogeneity.

Joanna Eberhart made it into my conference presentation, in which I spent a further fifteen minutes or so telling my audience of fellow educators about the link between my popular/unpopular satisfaction scores and the wonky veg of my other metrics.

I wanted to prove that teaching and learning done right is always going to be an asymmetrical affair; that if your core business is working alongside real people learning new and difficult things, you had to expect your metrics to be lumpy – especially if the institution you worked for enacted disingenuous student recruitment policies modelled after four plastic hippos.

More than this, I had the audacity to suggest that those high student satisfaction scores, so garlanded by senior leadership, were not the product of donuts, lollipops, or more outrageous acts of coercion, but the result of the very same teaching and learning culture that was fighting to keep representing the heterogeneity of our learners’ developmental journeys. I could see no contradiction in students who achieved their learning outcomes at the second attempt also returning scores of 100% satisfaction; why wouldn’t they feel satisfaction for a course that prioritised the quality of their individual learning journey over and above the university’s weakness for paths of lesser resistance?

A beat or so after I finished my presentation, the lecture theatre gave way to spontaneous applause. I wasn’t expecting that. In truth, I’d been nervous throughout, but yes, for a moment, it was like that scene in Dead’s Poet Society, when all the boys stand on their tables. It was my ‘I am Sparticus!’ moment, or as close to it as was possible, given I was in, um, Epsom and I’m no Kirk Douglas.

Okay, okay, so it wasn’t much like either of those dreamed-of Hollywood endings, but I’m telling you about it now, not because of how it made me feel (and if you want to know, it felt great), but rather because of the palpable sense of danger and bravery it seemed to take all of us that day just to speak up.

I Am Talking About You

The convenient thing about making cute analogies with science fiction B-movies is the implication that, while these stealthy enemies of diversity might look just like us, they are ultimately ‘not us’. Relax everyone, this threat to ourselves is extra-terrestrial. Indeed, you might be reading this as a fully fledged pod person yourself, but taking comfort from the fact I can’t possibly be talking about you because ‘pod people’ come from outer space. Well, make no mistake, I am talking about you, because really I’m talking about all of us.

As of now, there have been four adaptations of Jack Finney’s 1955 novel, The Body Snatchers, with each filmed version being interpreted in different ways; Siegel’s 1956 film is routinely seen as a metaphor for the fear of Communist infiltration and the loss of individuality, and, conversely, as a critique of the anti-communist witch-hunts incepted by Senator Joseph McCarthy. Twenty-two years later, Philip Kaufman’s version is understood as essaying suspicion towards institutional power in a post-Watergate world, but also as an elegy for the absorption of 1960s counterculture into the mainstream. Not surprisingly, with its story taking place on a military base, Ferrara’s 1993 re-telling offers up a commentary on the pervasiveness and control of military institutions over the lives of individuals. The Invasion, Oliver Hirschbiegel’s not-so hot 2007 remake starring Daniel Craig and Nicole Kidman, has something equally gloomy to tell us about the erosion of civil liberties post 9/11.

Actually, then, these stories are being interpreted in the same way, each of them offering up their respective cautionary tales on the pernicious effects of groupthink on the social, cultural, and intellectual life of entire communities. These body snatchers are not eroding our identities ‘from beyond’ but rather from within. These invasions begin not with interstellar spores, but with the ideas we choose to adopt and disseminate, and with the troublesome knowledge we elect not to live with.

In short, we seem to make easy victims of ourselves because we make easy targets.

Oh yeah, the other really important thing these narratives share is the way in which the swapping out of ‘people for pods’ takes place, for it is never enacted by force, hypnosis, or at the end of a ray gun, but by the simpler act of just closing your eyes to what’s going on around us: ‘They get you while you sleep.’

Home Again

I began this with a story about sleep; a small boy dressed in paisley pyjamas who shut his eyes for the shortest time—or so he thought—only to open them to find his home as repulsive to him as it was familiar. The ending of that story was a happy one; with the arrival of his parents and the restoration of this haunted house as home, the boy in the pyjamas experienced a vivid return to all that was most important to him. In vanishing like that, his home and his family also had the chance to appear to him again as newly beloved. If the uncanny has a usefulness, you might say it’s exactly this—how it produces, however briefly, a glimpse into the places we do not want to go and the realities we would well do without.

When those mannequins and waxworks unnerve us with what is so almost about their simulation of ourselves, they are surely reminders of who we are, what we value, what makes us, and what it really means to be completely alive.

I suppose that’s why I’m fascinated by the uncanny, and why these movies about body snatchers and robo-wives, with their downbeat and dystopian denouements, are amongst my favourite things: I get to shudder at these sorry, blighted communities, and I get to leave them too and decide to do things differently, to redouble my efforts—to resist.

And about those Hungry Hungry Hippos; I think the real reason mum and dad never bought that game for me, was not because I one night screamed the house down and scared them half-to-death, but because they thought Hungry Hungry Hippos was a divisive piece of shit with no educational benefit whatsoever.

Anyway, I think the pod people are mistaken as they sit where they sit, finding different ways to tell us, ‘There’s no one like you left’. They would know they were wrong about it too, had they been there; had they been there in that less-than-cinematic conference room, where a community of knackered educators once applauded an image of a wonky carrot, as we felt our home restored to us and, next, the beating of our hearts.

Originally published on Linkedin

Leave a comment