We Used To Call People Late At Night (2008) is one of my favourite things. Here’s why.

Recently, sitting opposite an old friend on a fast train, I talked with him about an animation I’d watched years before and many times tried finding again without success. It was such a slight film, I said to him, the shortest of shorts, a wisp, but even as I spoke of it, something began lifting the fine dark hairs on my arms.

It was black and white, I continued, a blink-and-you’ve-missed-it sort of a thing about a child making prank calls, and I told my friend how watching it that first time unnerved me perfectly, and how, sometimes, if ever I was feeling a bit dead-behind-the-eyes, it was to the half-life of this half-remembered film to which I often turned for inspiration.

A day or so later, I received an email. ‘I’ve found it’, my friend said.

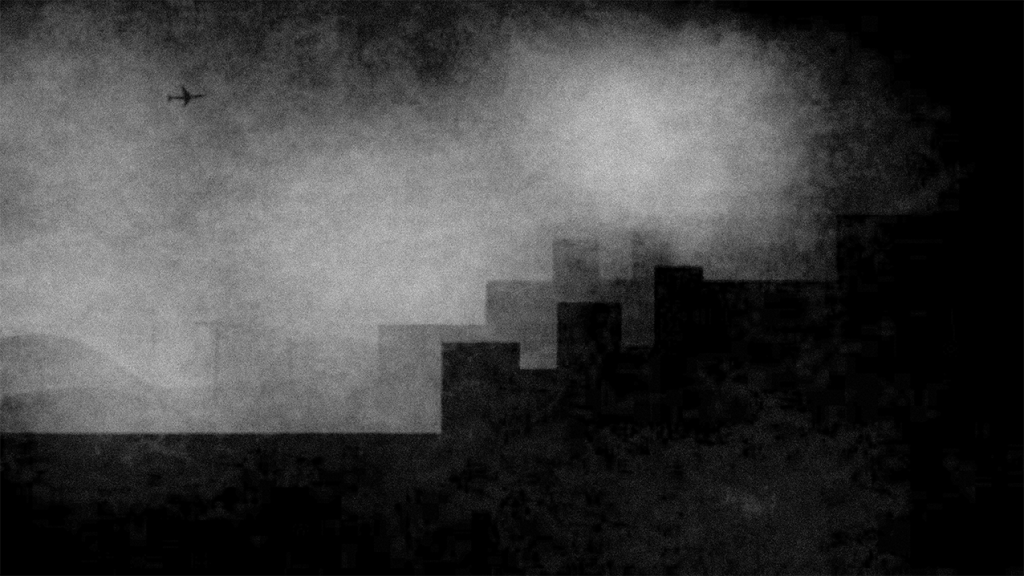

Made by Anna Shevchenko, Yoav Brill and Eran Hilleli, We Used To Call People At Night is one of those trick, stick-on holes you see in Road Runner vs. Coyote cartoons; you know the thing I mean, the black two-dimensional disc one character carries around like a rubberised bath mat, but which becomes abyssal and vanishing for the other character who steps on it. We Used To Call People At Night seems harmless enough, what with its thinnest of plots and flat animation, but don’t be fooled: it too produces a pit and drops you down it just as sharpish.

The story, such as it is, introduces us to some kid somewhere telling us how he used to phone strangers late at night. If a woman answers, the kid says, ‘Mum?’. If a man answers, he says, ‘Dad?’, and then the kid rings off, and we’re left imagining two unspooling realities; in one, another human being is feeling the sudden clutch of terror as they imagine the worst. In this reality, they are moving quickly through the silent house to check if their kids are actually safe in bed and not, in fact, spirited away to this someplace else at the far end of a telephone wire; or they’re phoning their now grown-up children, waking them in fright, saying, ‘Love?’, more lights coming on all over the world like tiny pricks of fear.

And even if these people don’t have children, they return to their beds to lie awake there. They’re imagining someone else’s child is in trouble and maybe this stupid kid on the phone was too drunk to dial the right number. So they’ve lost their wallet or missed the last train, no big deal, it happens, go to sleep.

Or maybe this kid is a runaway, summoning the courage in the dead-of-night to phone home at last? Or they were calling from the very edge of some vertiginous ledge with second thoughts? Or maybe this kid is lying alone in the dark with parts of them broken, this mis-dialled call their very last chance before a shadow falls across them and they’re disappeared forever?

Meanwhile, in the second reality, a bunch of kids are snorting with laughter, high on cola and their fingers orange from scoffing cheap snacks. These human beings are feeling completely alive right now, the blood whooshing in their ears. This is certainly one up from burning ants with a magnifying glass or pulling the wings off flies before feeding them to spiders. This is what real power feels like! Stupid fucking adults standing in their stupid fucking kitchens in their stupid fucking pyjamas! Stupid fucking parents, and maybe, as they set about dialling another random number, they fantasise about a world in which they can do whatever they like, and their fantasies are likely small and stupid, like eating breakfast cereal for every meal and burning down their stupid fucking schools.

Only this time when someone answers their fucking funny phone call, things go differently. This time, the recipient says, ‘Hello? Hello? David? Is that you? Where are you?’ and while we’re never told the film narrator’s name is ‘David’, the narrator’s name is David, I know it, so this is the moment you’re playing with a Ouija board in the old dark house and it’s all been shits and giggles until the glass spells your name. David says, miserably, ‘We never phoned people again’, and there’s a third reality now, the one in which David and his dumb friends are left staring at the phone as they might regard a coiled snake. In this reality, these same kids walk past forlorn public phone booths that suddenly ring out for them and them alone. In this reality, David stares up at all the wires above his head, menaced by their ubiquity and the way in which they’re into everything, and now whenever the phone rings in the house and his parents say, ‘David? It’s for you’, it is David feeling the clutch of fear, and it is David lying awake at night, and it’s David for whom the bell tolls, or rings at least.

We Used To Call People At Night is a short film in a long tradition, for this is ghost in the machine stuff. Sure, the voice that knows David’s name is obviously non-human and robotic, but this sinistered technology isn’t as operatic as the likes of The Terminator, Demon Seed or Megan. This is the quieter, uncannier stuff that situates in what we do not like about the temporal displacements of technologies that keep or duplicate or project our image and our voice. This is much more the haunted video tape of Ringu, the undeadness of our recorded voice and image and the nausea born from the realisation that everything we’ve ever transmitted lives on without us as white noise, drifting like skin-flakes.

Made back in 2008, We Used to Call People At Night pre-dates our very current discomforts with machine learning and generative AI, but it knows them too. Much of our zeitgeisty disquiet stems from the idea that this burgeoning intelligence, however extraordinary and/or lethal, has learned from us by listening in to our every conversation and surveilling our activities without our express consent. When I think about David staring at the phone, repulsed by the idea of this other intelligence’s unsolicited knowledge of him, I’m actually reminded of a night in the company of my own friends as we sat in the pub talking about snooker.

Significantly, snooker is a subject I never talk about, for snooker is as easily as depressing to me as Dad’s Army, Bergerac and Songs Of Praise, joining them in that category of drowsy entertainments synonymous with beige men and creeping senescence. I can’t remember why we were talking about snooker that night, and certainly we didn’t talk about it for very long. I likely made sure of that, but a short time later, when I was looking something up on my phone, the first suggested search result, apropos of nothing, was Stephen Hendry, a former world snooker champion…

There’s a very good reason We Used To Call People Late at Night isn’t called We Were Talking About Snooker In the Pub One Night (I refer you to my previous comment re. beige men and creeping senescence) and I freely admit this happenstance is hardly commensurate with David’s much creepier phone-related encounter, but this little incident chilled me. Putting my phone back down on the pub table, I eyed its black two-dimensionality with suspicion, reminded again of those sneaky black holes from those Loony Tunes cartoons. Who’s down there?, I wondered unhappily. I know you’re listening.

My husband and I live in a small end-of-terrace house and every now and then, kids will knock on our front door before haring off again into the night. There’s something uniquely unsettling about answering your front door to find no one is there. This may be one of those chicken and egg things, in so much as I’ve seen this moment in scary movies so often, perhaps I’ve been tutored to find it so. In movies, answering your door to find no one is there is nearly always a precursor to a gratuitous jump scare and/or a swiftly sticky end. Or is it because there’s something innately unheimlich about the Schrödinger’s cat-ness of an unexpected knock at the door?

Either way, answering the door to thin air is never a completely neutral experience, even though I’m now much more likely to meet these schoolboy japes with a sort of begrudging nostalgia. Much less so when some kid gives our door a really good kick last thing at night, which sets the whole house shaking and its inhabitants too. There’s a story about the late film director, William Friedkin, firing shotguns on the set of The Exorcist to ensure his cast was jangling with nerves as the cameras rolled. There’s nothing quite like a loud, unexpected bang from some unseen source to get your cortisol squirting. Afterwards, it always takes an intellectual effort to remind ourselves these kicks to our front door aren’t personal attacks, but rather as meaningless as what drives David and his mates to make those random calls. My husband and I know this. This is what we tell each other. This is what we tell ourselves.

So even though We Used To Call People Late At Night is a wisp of a thing, it puts me in mind of much nastier fare, of the brutish home invasion narratives of Funny Games or The Strangers or Them. A prank phone call doesn’t come close to the prolonged and awful torture in those films, and yet, We Used to Call People Late At Night shares with them what is awful about arbitrariness. It’s as the line goes in The Strangers, when Liv Tyler’s character asks of her assailants, “Why are you doing this to us?” to which they reply, ‘Because you were home.’

More than anything, We Used to Call People Late At Night makes me think about the Polish father and son who lived next door to us when I was growing up, and how, as kids, we thought of them as bogeymen, and how, during the long Summer holidays, my friends and I would knock on their front door. There I am, laughing my arse off behind a white Ford Capri, my tongue a vivid blue from raspberry ice-pops, and there they are, two immigrants in a crappy council house in a small provincial village who are now feeling just a little less safe on account of little old me.

Up until that strange robotic voice says, ‘David?’, I don’t think the kids in We Used To Call People Late At Night have ever had it cross their minds to imagine what it might be like to receive a phone call like theirs – and why should they? They’re young, which makes them unassailable narcissists. They’re going to live forever after all and no one they love has died yet, but I’m now at an age when, if the phone rings late at night, it’s as ill-omened as waking up to find a raven tapping its beak against your window.

Some of what I feel when I watch We Used To Call People At Night is pleasure certainly. A larger part is the gravid weight of my empathy, which is another way of saying We Used To Call People At Night makes me feel worried and guilty and old.

Mostly I relish this creepy little film because of the way it produces incipience, which is that special quality I’m always circling when I think about why I like what I like. We Used To Call People At Night shares this quality with Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World, and that quality is a sort of narrative resistance, a sensation I’d liken to the strain in your fingers as you fight to keep a light switch from being either on or being off.

In common with Wyeth’s painting, We Used To Call People Late At Night establishes a premise forever arrested by very dint of its brevity. We will never truly apprehend this story because it is so short, which means we will never quite be free of all the many things it could be.

For my part, I assume the robotic voice in We Used To Call People Late At Night uses the boy’s name because all this time it’s been waiting just for him. Just notice how desperate the voice sounds, how needy, though I’m tempted to call it hungry. I assume too if David had remained on the line for one moment longer, this thing at the other end would have traced his location – but then what? Come worming along the telephone wires to squeeze its way out of David’s receiver like strings of minced beef?

Then, moments after the call ends, we see a strange blue flash on the skyline and I get thinking about Stephen King, or rather the way one of those big fat books of his would start; with some average Joe, (but let’s call him David), discovering late one night that there are strange forces at work in the wires that bind us, an entity, a sentience, a predator, and whatever it’s doing out there and whatever it wants, it already knows his name.

Leave a comment