This business of photographing fields in as painterly ways as possible began at the beginning of the lock-down with a late afternoon trip to walk among improbably yellow fields of rapeseed. The challenge was capturing how it felt to be out there in that moment – overwhelmed by landscape and overloaded by a sort of greediness/desperation to keep the shifting effects forever. A few simple strategies helped produce more immersive results, like always omitting any obvious markers of distance or scale, and putting the focus far off at the edge of things with an eye to melting away the detail.

After the fields of gold, there came the scratchier grasses at Oare, followed by the ox-eye daisies, milky and glaucous in the thinning sunshine. Sometime later, we would visit the orderly blue of a wheat field and then an unexpected crop of blue-beaded flax. But it was our trip to the meadow at Knave’s Ash that really inspired my greed for in-camera impressionism. The weather wasn’t great, the sun buried behind an unwashed soft-box of cloud, and yet, as I viewed the resulting photographs later that night, I experienced a proper sugar-rush of delight and satisfaction. Something had happened at Knave’s Ash, a serendipity of light and breeze, and colours so numerous and soft, I couldn’t believe my luck. You can thank this set of photographs for everything that happened next, the zealous pursuit of specialness in other unadopted spaces, the continuing quest to transform something often-seen into landscapes ‘galaxical and vivid’ (so described by poet and fellow blogger João-Maria), and I’ve been lost to this pursuit of ‘painting with fields’ ever since.

When Francesca Maxwell put forward the title of a book by Rebecca Solnit for our most recent Kick-About, I smiled. The prompt A Field Guide To Getting Lost seemed ready-made for an individual looking for a jolly good reason to push these images further. More than this, here was an opportunity to counter one of the systemic failures of these images – their respective failures of movement and of sound – for how can any of these stubbornly still images hope to express the whiffle of the breeze playing across the stems and tassels of all this grass, or the hungry way my camera and I turned about in an up-against-it chase of fleeting light and restless composition? How to convey the different moods elicited by these different fields and by all the associations gathering around their images – the dissolving and dematerialisations at Knave’s Ash, the fibre-optic swish-and-swizzle at Hart’s Hill, and the meditative tapestries at Boughton Scrub..? Make a film was the answer. No, wait. Make three films!

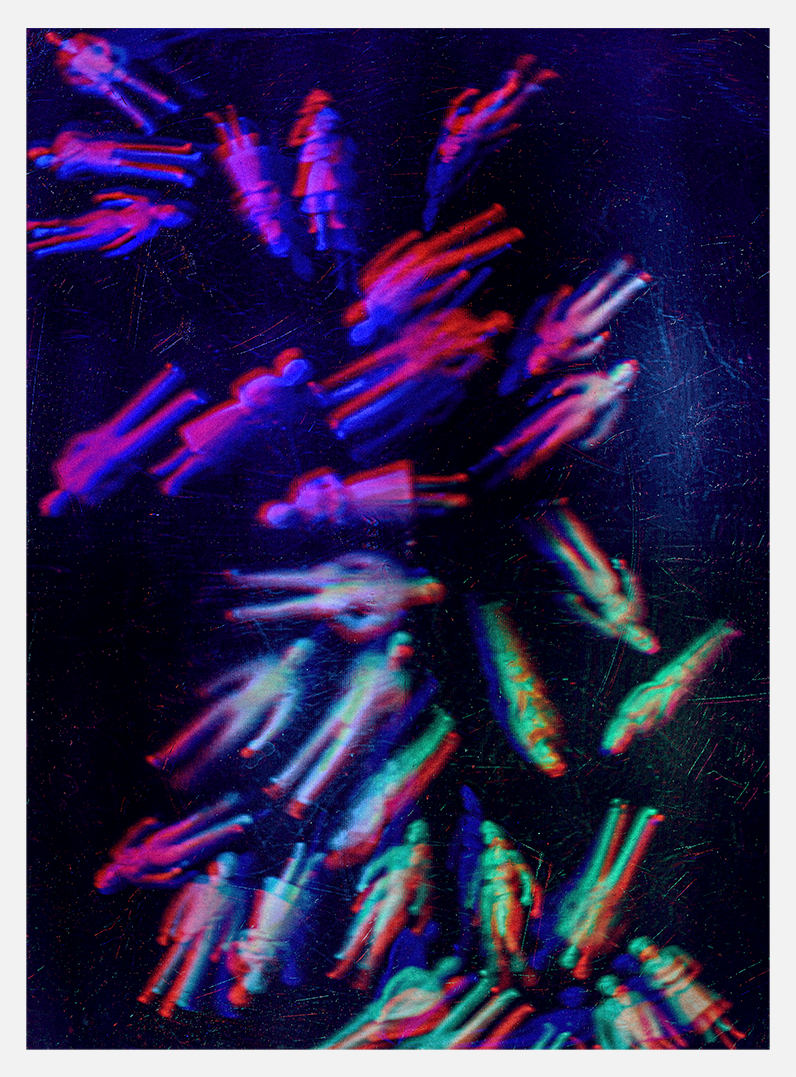

Bringing the meadow of Knave’s Ash into some semblance of movement was a simple job of long cross-dissolves and a suitably atomised choice of music, courtesy of Kevin MacLeod. The job here was mimic as sensitively as possible the diffusion of the images. When it came to trying to articulate the very different feel of Hart Hill, I had but a single guiding reference: Norman McLaren and Evelyn Lambert’s Begone Dull Care (1949), an animation created by painting and scratching directly onto the surface of the film in the service of giving visual expression to the jazz music of Oscar Peterson. My thinking around this film was less to evoke the ‘outdoors’ but rather the ‘indoors’ of my efforts to snaffle-up every last dart, arrow and filament of barley.

I know we were very lucky to find Boughton Scrub. A part of me suspects it only appears when you’re not looking for it, and if we went back to that peripheral place, we’d only find the sewage works and no evidence of those ox-blood coloured rumex spires or clouds of luminous thistle-flowers. For all the common-or-gardenness of the grasses and wild flowers in this scrubland, there was an unreality about this landscape. Even as I stood among it all, I knew it wouldn’t last, that I had to move quickly to steal as much of it for myself as possible. It was almost too colourful, more like some coral reef or martian landscape. The more I looked at the resulting photographs, the more they resembled zoomed-in details from Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights or like luxurious, too decadent wallpaper, or like tapestries hanging in the quiet chambers of some chivalraic folly. Meanwhile, my mind’s ear kept playing me lutes or harps, my mind’s eye showing me some soft-focused Burne-Jones maiden walking unhurriedly between the voiles of flower.

It will appear unseemly when I admit I have now watched the resulting film many times. I just find it immensely relaxing, cooling, quietening. I do not watch it admiringly, rather I just like going back there in the knowledge that it’s gone.

Leave a comment